“Unfiltered Little Prophets as Embodied Reality of Grace”

Humble Walk Lutheran Church

St. Paul, MN

By Derek Wu

Humble Walk Lutheran Church has a well-established—and warmly boisterous—online presence. The church most often communicates through a bustling Facebook page, full of frequent posts and comments from Pastor Jodi Houge and congregants. For all its activity, you would not expect the Facebook page to represent a community of around 40 congregants who dwell in a working-class neighborhood of St. Paul, Minnesota.

Humble Walk Lutheran Church has a well-established—and warmly boisterous—online presence. The church most often communicates through a bustling Facebook page, full of frequent posts and comments from Pastor Jodi Houge and congregants. For all its activity, you would not expect the Facebook page to represent a community of around 40 congregants who dwell in a working-class neighborhood of St. Paul, Minnesota.

After transitioning to primarily digital services due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the community has increased significantly in number, tallying up to 600-800 views per service. Yet throughout the rapid growth, the digital content remained minimally produced—most Sunday services are livestreamed by Pastor Jodi and her husband (a musician) on a webcam from their kitchen, and worship leaders often upload simple hymns with a guitar and conjure up humorous skits for the kids in the congregation.

Some services during this period of social distancing were livestreamed from an in-person gathering in the yard of Art House North, the space rented by the church. I was fortunate enough to attend the first in-person service livestream since the distancing policies were put into place. When I logged on, the camera was centered on the person leading worship. She sang and played her guitar by herself, and she was distant enough (and the video quality was bad enough) that I couldn’t really make out her facial features or complexion.

After she finished the worship set, the camera panned over to Pastor Jodi, who stood a few yards to the right of the worship leader. Between them was a table that appeared to be the communion table. There was a white tablecloth draped over it, and the tablecloth was splattered with colorful paint—as if done by Jackson Pollock. There was a cross and a jar on top of the table.

Pastor Jodi began to preach with a gentle yet unwavering and authoritative voice. She told the story of the woman denied by Jesus at the table, emphasizing the tenacity and courage of the woman to ask even for crumbs. I still couldn’t see the congregation, but I could hear scattered laughter upon lighthearted comments Pastor Jodi wove into the narrative. She concluded by proclaiming the open-armed nature of communion: “Not one person is excluded from the kingdom and from this table. I think when we gather around this table, around the weekly holy meal of wine and bread, that crumbs are enough. Even if we only demanded crumbs. [In our case,] saltines and juice boxes are enough. Amen.”

Then, Pastor Jodi asked of the congregants: “If there is something you have created, hold it up!” Pastor Jodi would later tell me the church provided air dry clay packets for anyone who wanted to create while they listened. This was “a long-held practice here—something for all ages to do with their bodies as they listen to the sermon.” Pastor Jodi began to speak to these “creators” by name. It sounded like she was mostly talking to kids. Her demeanor changed effortlessly from preacher to elementary school teacher. “Oooh, I love it!” she cooed. When the time of creation-sharing was over, Pastor Jodi proclaimed, “If you’re still working on your creation, you can wait until after the prayers of the people to share it if you feel rushed.” I assume that some children (or adults) had brought their art projects with them to do during the service.

Following all this were quiet moments of singing, prayer, and then the partaking of the Eucharist. As crickets chirped and the breeze blew softly through the trees on this idyllic summer day, I could hear soft prayers being murmured in the background by the congregants. And for some reason, this livestreamed communion—recorded thousands of miles away from me—felt weighty. Even though I could not see the congregants, I found myself reveling in the wonder of the moment as they transitioned to a response song.

The quiet moments were soon overtaken by a time for “milestones” and announcements. “A milestone,” Pastor Jodi explained in a bright, cheery tone, “is anything big, or small, that has happened in your life that you want this whole community to know about. Typically, we form a line. We’re going to do milestones a bit differently in this season. You’re going to raise your hand — ooh, fun! — and I’ll put the rock in for you.” Here, I realized that the jar on the communion table was for these rocks. Pastor Jodi continued: “So, maybe you’ve had a birthday, maybe you grew a job or grew a tooth, or lost a job or lost a tooth, we want to know!”

The quiet moments were soon overtaken by a time for “milestones” and announcements. “A milestone,” Pastor Jodi explained in a bright, cheery tone, “is anything big, or small, that has happened in your life that you want this whole community to know about. Typically, we form a line. We’re going to do milestones a bit differently in this season. You’re going to raise your hand — ooh, fun! — and I’ll put the rock in for you.” Here, I realized that the jar on the communion table was for these rocks. Pastor Jodi continued: “So, maybe you’ve had a birthday, maybe you grew a job or grew a tooth, or lost a job or lost a tooth, we want to know!”

As people shared their milestones, they were accompanied by a hearty “Milestone!” cheer by Pastor Jodi, the congregants, and the comment section on Facebook. Each sharing of a milestone was accompanied by Pastor Jodi throwing a rock into the jar on the communion table. Here are some of the milestones shared:

Someone turned 60 years old

A child, probably under 10, shared about a fun family vacation to Michigan.

Another child: “I moved here!” Someone who I assumed to be her dad chimed in: “I also moved here!” (Laughter and cheers followed this one).

Another child: “I turned five!” Pastor Jodi cheered: “Milestone and happy birthday!” (“Wow,” I thought. “Even the kids feel so welcome here on a Sunday morning—that is a difficult environment to maintain.”)

After milestones and announcements, the worship leader sang a song written by one of the congregants. My eyes widened—having served as a worship leader myself, I was struck by the willingness and vulnerability of a congregant to do such a thing. Then I remembered what I had seen on Humble Walk’s website—these congregants had recorded a “Humble Walk Album”! There was a paid artist-in-residence on staff. There certainly were artists among them—and it made total sense that the congregants would write songs for the church.

Soon, the service was finished, and I sat in silence. There were many factors contributed to my experience of warmth and awe, an experience I found hard to put into words. However, upon looking back through my notes, I recognized that my strongest emotional reactions had something to do with the children. The way Humble Walk “put the children at the center,” as Pastor Jodi would later explain to me—there was something raw, authentic, and heartwarming about taking communion in that unique context. The children gave me the impression that this was a warmly boisterous community.

Seeking to explain my vague reaction of warmth, I thought it would be a good idea to unpack some of the principles behind Humble Walk’s ecclesial traditions. I discovered that the church as a whole clearly values caring for those who felt that they did not belong in any other church or community. When I first loaded humblewalkchurch.org, I was immediately greeted with “Welcome. You already belong here” in large white text overlayed onto a slideshow of glimpses into church life. This was elaborated below: “If you are looking for a community . . . You are welcome, because you already belong here.” The more I asked Pastor Jodi and congregants about this value of “welcoming those who didn’t belong,” the more it appeared to me that this was a core mission of the church. Pastor Jodi explained to me that for many of those who visit, “it’s the ‘last gasp’ try at church—so they come in expecting they’re going to hate it.” Mel, a newer attendee at Humble Walk, explained to me that she and her spouse were “cradle Catholics” who never thought of themselves as “church people.” Another congregant explained that, before Humble Walk, he had stopped going to church because of his sexual identity. One longtime congregant said lightheartedly, “We’re a diverse bunch of—kind of, um, . . . I’m just going to say it—like white weirdos. And that’s just largely who we are.”

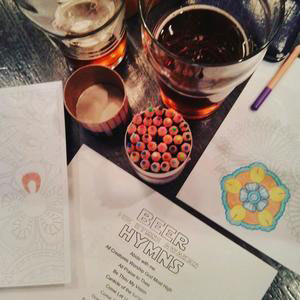

The value of “welcoming those who didn’t belong in church” extends into Humble Walk’s traditions and practices. Instead of spending their resources on a church building, Humble Walk spends a great deal of time in “the heart of our community, where people already are, where people already liked to gather.” For example, church members are self-proclaimed “bar people.” Before the pandemic, the church hosted a monthly event called “Beer and Hymns.” Led by musicians from the church community, congregants and curious onlookers gathered at Shamrock’s Irish Pub and sang old hymns with “reckless abandon,” often to the strums of a single guitar. Pastor Jodi remembers the first Beer and Hymns clearly: as the crowd in the back room of a bar “burst into four-harmony”—unburdened by the loud church organ that usually drowns out peoples’ voices—Pastor Jodi “burst into tears because it was so gorgeous and weird. [The musician] and I couldn’t believe people wanted to do it. The whole thing was explosive.”

After this first event, the gathering increased exponentially in number over the years. “Prompted by the Spirit,” Pastor Jodi describes, friends invited friends, who invited more friends. And “people would come in, and they would weep . . . because of the communal singing, because they’re doing it in a bar, because they’re drunks hanging out at the doorframe, because this is the song that their grandmas sang to them all growing up, and they didn’t even realize they needed the song or the words.” Nowadays, the event consistently attracts 100+ people—Christians, ex-Christians, and non-Christians—to sing together. And since Pastor Jodi tells her congregants that “they will know us by our tips,” Humble Walk and Shamrock’s Irish Pub maintained a thriving partnership and share a mutual recognition of value. Waiters at the bar know and love the clean and polite “tenants” from Humble Walk, and the managers offer the space for various church events such as Christmas pageants.

I asked Pastor Jodi to tell me the core values that sustained these sorts of practices. She responded that the main thing is grace. “You don’t have to get it together to come, you don’t have to suddenly stop smoking and become a healthier person to come. You don’t. You don’t have to be mentally stable to come. You don’t have to be financially stable to come wherever you are. You don’t have to even be a Christian to come.” It was her hope as pastor that the church would exist as an “embodied reality of grace.”

Pastor Jodi continued to explain that this form of grace has been a major part of Humble Walk’s ecclesial life. “I would say for the first five years, most of our folks would not claim they were Lutheran for sure. And I’m not even sure if you said as an exit poll leaving worship, ‘Are you a Christian?’ I feel that they couldn’t even answer that question, really. But they’re praying there. They were stumbling forward for communion—a bit of bread and a bit of wine. They were asking me to talk to their kids about baptism, and they’re practicing all the tenets of Christian faith.”

It became clear to me that this church shared some common missions, or purposes, that were unique to Humble Walk. One, for example, was to minister to those who had been excluded or hurt by the Church in the immediate community of St. Paul, Minnesota. I found strong evidence of this common ecclesial purpose in a “COVID Response Team” meeting. In October, Pastor Jodi assembled a team of congregants to address the difficulties that would come with church shutdowns in the winter. Advent was coming, and the church needed a plan. There were people in the community who desperately needed in-person community; however, it was safer for the community as a whole for the church to cancel in-person events. What resulted was a practical dilemma that pushed Pastor Jodi and congregants to articulate Humble Walk’s “goals of care,” a term used by a hospice nurse on the response team. In other words, the team discussed the purpose of their ecclesial existence—and the team attempted to apply Humble Walk’s ecclesial purpose to the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Congregants in that meeting explicitly confessed the core ecclesial values behind Humble Walk’s practices and traditions. Morgan, the nurse on the team, said that “theologically . . . telling somebody that we’re having worship, but you can’t come, we don’t have any room for you, pushes on a lot of bad shit for me. And that is not the kind of church Humble Walk is. Some churches say, we don’t have worship until everyone can come. People can choose anyway, but for people who are in crisis, I would never want to say there isn’t room for you.” Matt, a university professor, chimed in with strong agreement: “That is a very good point, and I fully support it,” he said. “That is the starting point—how can we include and invite people without needing to turn anyone away?”

Congregants in that meeting explicitly confessed the core ecclesial values behind Humble Walk’s practices and traditions. Morgan, the nurse on the team, said that “theologically . . . telling somebody that we’re having worship, but you can’t come, we don’t have any room for you, pushes on a lot of bad shit for me. And that is not the kind of church Humble Walk is. Some churches say, we don’t have worship until everyone can come. People can choose anyway, but for people who are in crisis, I would never want to say there isn’t room for you.” Matt, a university professor, chimed in with strong agreement: “That is a very good point, and I fully support it,” he said. “That is the starting point—how can we include and invite people without needing to turn anyone away?”

Pastor Jodi concluded the meeting with her two takeaways and a short anecdote. One, “can we meet safely?” and two, “can we do this in a way that no one gets turned away?” She explained how both these questions are equally important because even just the past Sunday, a person showed up at the church for the first after getting out of rehab. Pastor Jodi shared how devastating it would have been if they would have had to “turn him away.” She continued, “And that’s true for so many people who are coming to this very particular community—people who are coming with baggage and skepticism.”

After this meeting, I gained assurance that Humble Walk shared a common mission unique to their context—to minister to those who had been excluded or hurt by the Church in the immediate community of St. Paul, Minnesota. I found that I could phrase this sense of a common mission in the words of our project’s hypothesis. Perhaps the congregants and the pastor share common “images” of Humble Walk as a church. In other words, the congregants and the pastor draw from a common imagination of what Humble Walk should be and what Humble Walk should not be.

Further conversations with Pastor Jodi and Humble Walk congregants helped me connect Humble Walk’s shared imagination with what I had witnessed in the digital livestream of church. As it turns out, I was right to guess that there was something special about the children. When Pastor Jodi organized Humble Walk’s first gathering, more than half of those who showed up were children. In the context of Humble Walk’s particular community, children were the most vulnerable. Pastor Jodi explained her philosophy to me. In the beginning, she wrestled with other models of children’s ministry. One model was “to keep them busy so that they’re quiet, so that the adults can do the adult thing in worship.” Another model is “to send them off to their own thing so that they can have exclusively children’s time while the adults have adult time.” Pastor Jodi preferred an integrated model:

Theologically, I wanted children at the center [in order] to move at the pace of the most vulnerable. That’s gospel, right? To turn things upside down. It’s not the brightest, the strongest—we’re going to put the most vulnerable in the center and attend to what they need and move at their pace. In our community, that was the children. They’re the most vulnerable ones in the room. So, what is it that they need in worship? And if they’re engaged, then their parents can engage. If they’re engaged, then the whole community pays attention to what they’re paying attention to. And then it leads to all sorts of gorgeous moments of a three-year-old serving communion bread and people arriving who had been denied communion until they were a certain age, until they understood the theology, until they had taken all the classes. And here is this toddler, basically, handing them the body of Jesus. And I’m here for it. That is good church to me.

What resulted from Pastor Jodi’s integrated model was a public image of her understanding of a “good” or “ideal” church—represented by public representations such as the three-year-old serving communion. And congregants are well-aware of this image. I asked a focus group, “What do you expect when you think of Humble Walk?” One of the “cradle Catholics” mentioned earlier responded without hesitation: “Children crying and laughing in the middle of a service. I think that’s one of the things that really makes the atmosphere. There’s a lot of little ones in the Humble Walk community that are just allowed to be small during a service. If they will be vulnerable, we will be vulnerable. If the kids go up to milestones, eventually, more adults go up to milestones. They are part of this community. We are all part of this community.”

One congregant shared a heartwarming story about a little girl who often goes up to stand by Pastor Jodi while Pastor Jodi is preaching. At one point, Pastor Jodi held out her hand in order to bless the community—and a picture was taken of [the girl] holding her hand out alongside Jodi, “And all of a sudden, we have [this little girl] and Jodi blessing the congregation.” Her voice breaking, she recounted, “And it still brings tears to my eyes, actually, because it wasn’t a distraction. It was—as Jodi said—the most holy moment.”

Another congregant shared a moment when the children were acknowledged—deservedly so—as a distraction. “It was an effort to remind us that life is distracting, right? It’s as if we’re supposed to find God in the daily things. Our work life, our home life, brushing our teeth, taking a shower, riding the bus, God’s there for all of that stuff. And if we can still be distracted in the middle of a church service and still find a way to focus on God, then we can learn how to do that [in] the rest of our lives, too.”

In a separate interview, I asked Jean, one of the first congregants to attend Humble Walk, to give me a story about what Humble Walk was all about. Her answers tie the themes of my portrait together:

When I went to my first worship service at Humble Walk, we were still at a storefront. And I remember putting on khaki pants and a sweater and getting dressed for church. Because in my mind, that’s just what you did. And I didn’t know. And we walked in, and I was like, “Oh, people just actually come as they are. Jeans and t-shirts from work.” And then there was two things that happened during that worship service that made me know that this was right. Jodi’s daughter was super tiny at the time and had come to church in some kind of Halloween costume. It was like a cat, or an animal, or a tiger. And it was nowhere near Halloween. And at one point, Jodi was in the middle of preaching, and Mae comes up to her and needs her mom at that moment. And Jodi, without skipping a beat, reached down and scooped Mae up, put her on her hip, and kept going with what she was doing. And I just thought, “That is so flippin’ cool!” That Mae wasn’t brushed away by anybody, her dad didn’t come up and get her. She just needed her mom, and then she was fine the rest of the time. I just thought that was so beautiful, and that acceptance and love of children has continued, just letting them be and do and just scooping them up and going on with what you need.

Her second story detailed a colloquial phrase unique to Humble Walk— “no sneaky Jesus.” Since the church is mostly made up of those who have grown up with negative experiences with Christianity, there is a strong, collective aversion to anything that seems disingenuous. For example, they did not want to invite people to the park “and have some games and let’s preach the gospel! Guess what? He loves you!” Humble Walk’s aversion to this sort of stealthy evangelism—what I understood to be the practice of baiting people into hearing a message about Jesus—was so strong that Jean shared about a moment of panic when someone began to pray for a meal during a community event. “We just wanted to create a genuine community and honestly get to know our neighbor,” Jean expressed. “And we’ve all had those experiences—I definitely have—where it’s been sneaky Jesus, and it doesn’t feel good.”

The phrase “no sneaky Jesus” encapsulates the sort of community Humble Walk aims to be. They seek to create a genuinely welcoming and safe space for the vulnerable in their community. There are no hidden agendas. They show up to church wearing work clothes, bearing tattoos and dreadlocks. There are no obligations or expectations—the church even boasts a “no membership” policy as an open-armed posture of invitation to those who have been scarred by tribalism. This raw, authentic, genuine display of love is modeled every Sunday, when Pastor Jodi figuratively and literally places “the most vulnerable in the center and [attends] to what they need and [moves] at their pace.” So, on Sunday at Humble Walk, Jesus does not cast the children and their distracting tendencies off to a separate room. Rather, Jesus invites them to be who they are among the community, no matter the interruptions that come with crying, laughing, or their simple need to be with mom while she’s busy preaching. This is but one way through which the church exists as a warmly boisterous, embodied reality of God’s grace to the vulnerable. And the public expressions of this ideal present public images or lived realities that cultivate the congregation’s theological and ecclesial ideals. Congregants use or draw from these images in their pursuit of Christian virtue and love. The children are the models—or, as Pastor Jodi puts it, the “unfiltered little prophets”—of the community’s “goals of care.”